Everything's a CASE statement!

Just a quick public service announcement:

Yes…I know it’s a “CASE expression” and not a “CASE statement”.

I’ve now received quite a few responses to this post saying nearly the same thing…“Not to be pedantic, but it’s a case expression, not a case statement”.

Yes…Thank you, you are correct, it is an “expression” not a “statement”.

When I originally posted it, I considered fixing the title, but changing the title also changes the URL. So, this PSA is my compromise. And as far as SEO goes…it appears most people search for “sql case statement” anyway.

Exhibit A:

Back to the post

Everything’s a CASE expression!

Well…not really, but a handful of functions in T-SQL are simply just syntactic sugar for plain ol’ CASE expressions and I thought it would be fun to talk about them for a bit because I remember being completely surprised when I learned this. I’ve also run into a couple weird scenarios directly because of this.

For those who don’t know what the term “syntactic sugar” means…It’s just a nerdy way to say that the language feature you’re using is simply a shortcut for another typically longer and more complicated way of writing that same code and it’s not unique to SQL.

Going from (what I assume to be) most popular to least popular…

COALESCE

Behind the scenes when you’re using COALESCE what exactly do you think is happening? If you’re use to working with something like C#, you might think it’s some sort of generic method with overloads like…

T COALESCE<T>(T p1, T p2);

T COALESCE<T>(T p1, T p2, T p3);

T COALESCE<T>(T[] p);

And then behind the scenes when your plan is compiled, it’s just picking some overload of an internal function…right? Nope. In reality, COALESCE(x.ColA, x.ColB, x.ColC), is translated into this:

CASE

WHEN [x].[ColA] IS NOT NULL

THEN [x].[ColA]

ELSE

CASE

WHEN [x].[ColB] IS NOT NULL

THEN [x].[ColB]

ELSE [x].[ColC]

END

END

What about ISNULL?

You might be wondering to yourself…“is ISNULL is the same way?”

Nope…

In the execution plan, it’s still just isnull([x].[ColA],[x].[ColB])…well, unless x.ColA is NOT NULL, in which case it’s smart enough to just ask for x.ColA since the ISNULL is unnecessary.

Unfortunately, COALESCE does not seem to have this optimization, even when the first column supplied is NOT NULL, it still converts to a CASE expression…I would hope y’all aren’t using ISNULL/COALESCE when the first column is NOT NULL anyway 😉.

So now that you know this about COALESCE and ISNULL…that might help explain why they handle data types differently. Where ISNULL always returns the datatype of the first expression (the check expression), whereas COALESCE returns the datatype of the highest type precedence among all the expressions, which is the same behavior as CASE.

IIF

These next two are pretty short and sweet as their CASE translations are straightforward.

When you use IIF(x.ColA > 10, x.ColB, x.ColC) it translates to:

CASE

WHEN [x].[ColA] > (10)

THEN [x].[ColB]

ELSE [x].[ColC]

END

NULLIF

When you use NULLIF(x.ColA, 0), it translates to:

CASE

WHEN [x].[ColA] = (0)

THEN NULL

ELSE [x].[ColA]

END

You might notice that the check expression is copied twice in this CASE expression. This opens up a problem when you use non-deterministic functions. It’s probably pretty rare to run into this situation with NULLIF, but here’s an example:

SELECT NULLIF(SIGN(CHECKSUM(NEWID())), 1);

The expression SIGN(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) will randomly pick either 1 or -1. So the expected behavior is that when the expression evaluates to 1, the NULLIF will catch that and return NULL. So in theory, it should NEVER return 1…but, if you run it, it does. And it’s because the check expression is copied multiple times, which means the randomization is also run multiple times.

Here’s what it looks like…

CASE

WHEN SIGN(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) = (1) -- Returns -1 so it evaluates to false

THEN NULL

ELSE SIGN(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) -- Re-runs this expression, which returns 1

END

So there are cases where it will return 1 when your expectation is it shouldn’t.

CHOOSE

This final function is probably the least used, but it’s also one of my favorites. Most of the time I use it, it’s for a fun reason. CHOOSE also has the same issue you run into with NULLIF due to how it generates the CASE expression.

A sample usage of CHOOSE is CHOOSE(x.ColA,'Foo','Bar','Baz').

For those who aren’t familiar with using CHOOSE, basically this is saying…if x.ColA is 1 then return “Foo”, if x.ColA is 2 then return “Bar”, etc.

If I were to ask you how this gets translated into a CASE expression…you might think it looks like this:

CASE x.ColA

WHEN 1 THEN 'Foo'

WHEN 2 THEN 'Bar'

WHEN 3 THEN 'Baz'

ELSE NULL

END

And if that were that case (heh, pun intended)…I think that would be ideal…Unfortunately, that’s not what happens. Instead, this is what it looks like in the execution plan:

CASE

WHEN [x].[ColA] = (1)

THEN 'Foo'

ELSE

CASE

WHEN [x].[ColA] = (2)

THEN 'Bar'

ELSE

CASE

WHEN [x].[ColA] = (3)

THEN 'Baz'

ELSE NULL

END

END

END

😢

The issue here is that our check expression is copied multiple times rather than being used once. Which means, if your check expression is not deterministic within the query, you could run into some weird issues just like we did with NULLIF.

For example, I’ve used CHOOSE in the past to act as a sort of “round-robin” picker. For example, maybe I have some sort of EventTypeID and I want to pick one at random for generating a test script. So I’ll write something like this:

DECLARE @RandEventTypeID int;

SELECT @RandEventTypeID = CHOOSE(ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())%5)+1, 1, 2, 5, 7, 21)

SELECT @RandEventTypeID

ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())%5)+1 will pick a random number from 1 to 5. So the expected behavior of the script above would be to return one of those EventTypeID values at random…But that’s not what happens. Try running it yourself, and you’ll see it occasionally returns NULL.

Here’s why:

CASE

WHEN (abs(checksum(newid())%(5))+(1))=(1) THEN (1)

ELSE

CASE

WHEN (abs(checksum(newid())%(5))+(1))=(2) THEN (2)

ELSE

CASE

WHEN (abs(checksum(newid())%(5))+(1))=(3) THEN (5)

ELSE

CASE

WHEN (abs(checksum(newid())%(5))+(1))=(4) THEN (7)

ELSE

CASE

WHEN (abs(checksum(newid())%(5))+(1))=(5) THEN (21)

ELSE NULL

END

END

END

END

END

Just like with NULLIF, that check expression was copied over and over, which means each time it is evaluated, it generates a new random value.

So how do we fix/avoid this? Don’t put your random expression directly into CHOOSE (or NULLIF), you need to create an alias for it or use a variable, like so:

DECLARE @RandEventTypeID int,

@RandSeed int = ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())%5)+1; -- Computed first, one time

SELECT @RandEventTypeID = CHOOSE(@RandSeed, 1, 2, 5, 7, 21)

SELECT @RandEventTypeID

-- OR if you need to do it for multiple rows...

SELECT CHOOSE(x.RandSeed, 1, 2, 5, 7, 21)

FROM (VALUES (1), (2)) t(foo)

CROSS APPLY (SELECT RandSeed = ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())%5)+1) x; -- Computed first as a "Compute Scalar" in the plan, then passed into CHOOSE

In both of those cases, instead of copying the random expression, the random expression is computed first and then later passed into CHOOSE as a constant value.

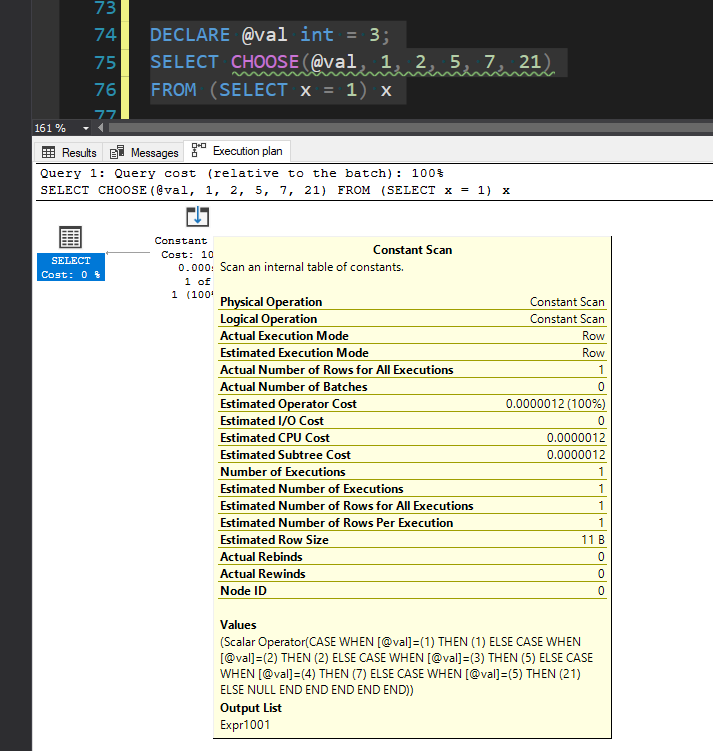

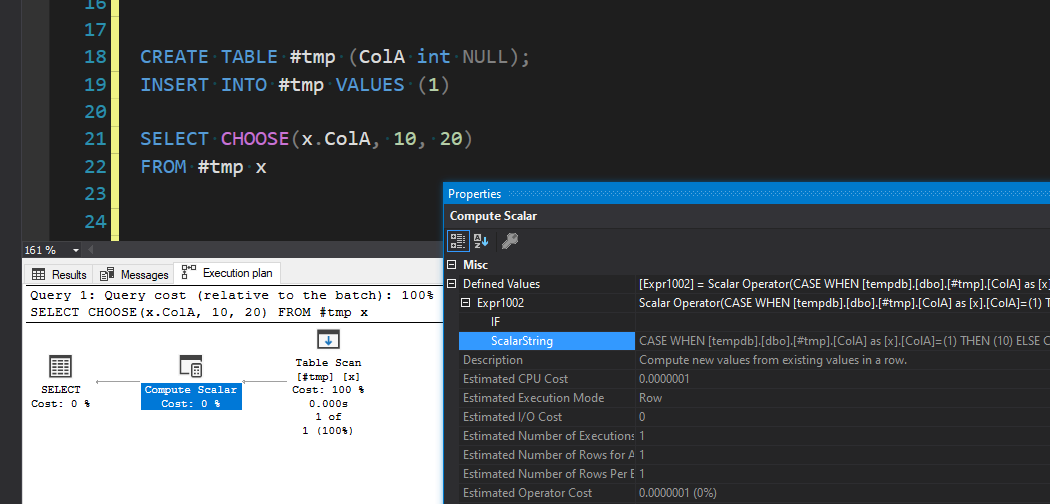

How do you see this for yourself?

Rather than pasting a bunch of screenshots in for every example, I’m just going to do it once here.

If you want to see this for yourself, there are two thing you need to do.

- Ensure you’re testing on a query with a

FROMclause, otherwise SQL Server won’t generate an execution plan. I’m sure there are exceptions to that, but at least in regard to building the small test cases for this post, I had to make sure each query had aFROMclause, even if it was something small likeFROM (SELECT x = 1) x. - Enable “Include Actual Execution Plan”

Run your test query:

CREATE TABLE #tmp (ColA int NULL);

INSERT INTO #tmp VALUES (1)

SELECT COALESCE(x.ColA, 10)

FROM #tmp x

Then take a look at the execution plan, and view the properties for the operator (there should only be one or two if it’s one of these test queries).

This is the most consistent way to see it. I’ve found that depending on the query, you might also be able to see it in that query text preview under “Query 1:”, as well as in the operator stats pop-up, like this: